The Man with Two Minds

John Haskell’s fiction launches expeditions into the murky territory of the self. Jascha Hoffman reads his new novel, the story of one man’s path to enlightenment via Steve.

Out of My Skin

John Haskell

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Dh130

John Haskell’s fiction revolves around questions that have long concerned both novelists and philosophers: Can we truly express how we feel? Who are we and how do we know? Can we change ourselves, change what we desire? While seeking answers, Haskell often dispenses with the usual trappings of fiction; in his work, the plot is typically not the main attraction. “I actually think of them as essays,” he once said of his stories.

The pieces in Haskell’s first book, the short-story collection I Am Not Jackson Pollock, were patched together from the lives of famous artists like Glenn Gould and John Keats and movie stars like Janet Leigh and Orson Welles. They floated between the public identities of these celebrities and confabulations of their inner lives, showing them trapped in the outsize roles they had created. Haskell’s voracious empathy also extended to cornered creatures like Laika, the first dog sent into space, and Topsy, a man-trampling elephant electrocuted in 1903, who he imagined facing their own problems of self-expression. “She could think and feel, but she couldn’t express herself because the language inside of her was elephant language,” he says of Topsy, “plus it was inside of her.”

These stories did not skimp on melodrama. They often paused at the moment their protagonists prepared to jump from a ninth-story window or immolate themselves on the steps of the Pentagon. Haskell would take a handful of these freeze-frames and alternate between them to create an aura of suspended catastrophe. But the results were never grim; Haskell displayed a gift for what one reviewer called “emotional ventriloquism”. When he spoke through those whose mortal predicaments did not allow them to speak, he was pursuing his own spiritual agenda, gently working through the problem of suffering, the limits of desire, or the nature of the self.

Haskell’s debut novel, American Purgatorio, took the road novel in a strange new direction. It told the story of a man named Jack who, abandoned by his wife at a gas station in New Jersey, sets out to drive across the United States to find her. What starts as an ordinary story of the pursuit for a missing person soon dissipates into a wandering picaresque. As he meets a series of American losers, Jack longs for his lost wife, seeing her likeness in the faces of strangers by day and reliving their tender moments at night. Eventually it becomes clear that Jack’s memories are fading and his sense of purpose is growing dim. For reasons that remain mysterious until the final pages, his mission drifts from finding his wife to purging himself of desire for a person he can only half remember.

To an even greater extent than Haskell’s short stories, American Purgatorio is propelled not by events but ideas. Haskell asks again and again what it means to need another person – and what it would mean to lose not just that person but the very need for human attachment. That he breathes life into an inquiry this abstract is remarkable. Even at his most explicitly philosophical, he casts an spell over the reader, thanks in large part to a delicate prose style whose casual tone belies its conceptual rigour.

In Haskell’s slim new novel, Out of My Skin, the existential stakes are even higher. The plot of this little book would barely sustain one episode of a mediocre sitcom, but it is packed with metaphysical heft. In the end it is a fable about the promise and perils of a desire that seems ubiquitous in contemporary life: the desire to reinvent oneself.

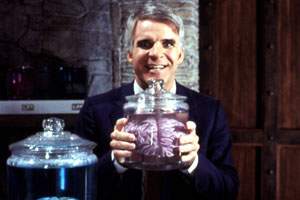

One might miss all this from a quick synopsis. Like its predecessor, Out of My Skin is about a struggling writer named Jack who, after losing his lover in New York, heads to California to start a new life. As the book begins, Jack has moved to Los Angeles to write about movies. After profiling a man who specialises in the impersonation of Steve Martin, Jack casually makes his own attempt to speak with what he imagines to be Steve Martin’s “come-what-may, devil-may-care joie de vivre” and to carry himself with a gait that looks like “a cross between dancing and staggering”. As he gets used to this new posture of self-assurance, his habitual awkwardness falls away. After allowing his new alter ego to attract an ex-dancer named Jane, Jack is essentially reborn as an incarnation of Martin, bleaching his hair and cultivating a practice he calls “the art of continuous Steve”. Once he has begun a relationship with Jane, he begins to see his old self as a hindrance.

It is not hard to see why Jack would want to lose his native self. He seems to lack a basic emotional sense, and generally discovers his own feelings only by observing how the rest of the world responds to his actions. When Jack is first introduced to Jane, he tells us: “I sat with my back straight, my collarbones extended, and I looked into her eyes in what I hoped was a meaningful way”. Recounting their jittery first date, arranged on false pretences, he remarks: “I was feeling a tightness in my chest, which is usually an indication that I’m about to do something or say something to spoil an otherwise enjoyable experience.” Jack is essentially locked out from his own soul, and he needs shelter.

His honeymoon with his assumed identity does not last long, however. Within a couple of weeks he resents the mask of Steve for trapping him in a relationship he hasn’t earned, and resents Jane for being “a trigger for the Steve in me”. Eventually he learns to accept the small part of himself that has not been crowded out by this false persona. Steve falls away, and so does his relationship to Jane. “We had drifted apart, not for lack of affection,” he says, “but for lack of Steve.” This is Haskell’s take on the traditional love triangle: Boy meets Steve, Steve gets girl, boy loses Steve and, with him, girl.

Whether one is charmed by this screwball conceit, the book’s principal delight is the voice that Haskell lends to Jack from his halting first line: “What happened to me was – not me, but what happened – I’m from New York originally...” (we later learn that he is from California). Haskell’s prose has the halting cadence of conversational speech, perhaps because he worked as an actor and playwright in Chicago in the 1980s. Many of his early stories were first performed as monologues, and from his radio broadcasts and online recordings one gets the sense that his works are meant to be heard as much as read.

Unlike other practitioners of what might be called overheard prose, most notably David Foster Wallace, Haskell’s tone is consistently reserved: distant but not cold, as if Jack were observing himself from another planet and reporting back. This approach is often methodical to the point of redundancy and can be deliberately, maddeningly vague. (“I went into the actual airport building, and we all know what airports look like, and this one looked like that.”) But at its best Haskell’s prose has an unnatural fluency that allows him to use ordinary language to express extraordinary thoughts.

As the book opens Jack has been lowered in a stainless steel cage into shark-infested waters for an article about marine biologists:

“I was aware of something, just beyond my vision. And when I say aware, I mean I was sensing, from the shark, a kind of communication. And since the most rudimentary form of communication is the expression of desire, I was sensing the shark’s desire. And since one of the things it was desiring was my annihilation, I can’t say there wasn’t a certain amount of fear. What I was trying to do was reach out through the fear, and communicate with this thing... I wanted to tell the shark that I understood what it wanted, and that I accepted what it wanted.”

Jack’s painstaking explanations often veer off into non-sequitur, or dead-end into contradiction; in these lapses one gets the sense that he has let loose some deeper truth about himself – about all selves – by mistake. One almost doesn’t notice these extraordinary manoeuvres on Haskell’s part because Jack’s voice has such a strange immediacy.

This may begin to explain why Haskell can afford to stray so far into the esoteric without losing his poise. On seeing the original Steve Martin impersonator win over a crowd of children at a birthday party, Jack remarks: “People who have the gift of letting go of themselves enjoy the gift because, by letting go of who they are, they can afford to let go of what doesn’t work. And the trick, it seemed to me, is to have something waiting, another self or another way of being, something, so that in the moment of letting go, in the sensation of that sense of nothingness, there’s something to hold on to.”

As he weaves these gauzy ruminations into the fabric of events, it becomes clear that Haskell is not aiming for New Age satire. He is composing an existential pilgrim’s progress, a manual for liberation from the shackles of self imposed by the world.

In fact, Out of My Skin has something of a Buddhist streak. Jack talks about meditation and mindfulness and earnestly tells us that he “wanted to reach out past all the façades of being”. (These overtones were also there in American Purgatorio, with its preoccupation with non-attachment.) When, midway through the novel, Jack trots out the Buddhist concept of anatta, or “no self”, it reads like a statement of purpose. We may as well be sitting on a mountaintop reading the Lotus Sutra by the time we get to the book’s spiritual climax, arguably the finest cookie-based enlightenment scene since Proust.

Before this unlikely moment of revelation arrives, however, Jack’s journey into selflessness is interrupted by a series of vignettes from the golden age of Hollywood, which reframe the action in thought-provoking ways but slow it down in the process. One can hardly blame Haskell for trying to recapture the magic of his early stories, which darted so brilliantly between the public and private lives of midcentury celebrities. But the asides – miniature discourses on films like Double Indemnity and Sunset Boulevard – become more of a distraction than a guide.

Readers looking for philosophical context are better off returning to Haskell’s magnificent early stories, which anticipate many of the concerns of Out of My Skin. The predicament of a mind split in two is precisely the subject of the title story of I Am Not Jackson Pollock. When the painter finds himself in a tavern, trapped in his authentic self as he watches his own vainglorious doppelganger seduce a young female acolyte, we are presented with an internal tug-of-war much like that between Jack and Steve. The scene puts a dark spin on a line attributed to Cary Grant: “Everyone wants to be Cary Grant. Even I want to be Cary Grant.”

It is hard to match the bluntness of these early stories. But what Haskell’s novels lack in dramatic power they recover in speculative precision. These are not so much stories as vehicles for building theories about what it feels to be constantly seeking out the contours of one’s self in the world. As Haskell’s sublimely dull prose comes alive, we have the choice to surrender to it. Once we do, we may feel ourselves inhabited by a foreign spirit, distant but compassionate, trying to describe some of our most persistent habits of mind so we might let go of them.

Jascha Hoffman writes for the New York Times and Nature. He lives in Brooklyn.