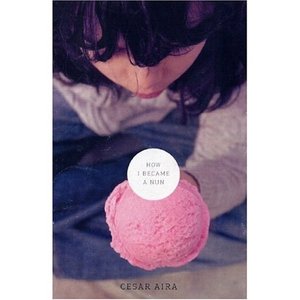

HOW I BECAME A NUN

By César Aira.

Translated by Chris Andrews.

117 pp. New Directions.

Paper, $13.95.

César Aira is a 6-year-old Argentine girl whose first taste of strawberry ice cream is tainted with cyanide. “I was a devoted daughter,” she says as she lifts the spoon to her lips. “Dad could do no wrong in my eyes.” After she retches, though, her father flies into a rage and murders the ice cream vendor, and the child collapses into a monthlong toxic delirium. She wakes in a hospital bed to a doctor who asks, “And how are we today, young Master César?” Lucky to have been one of the survivors of an unexplained wave of food poisoning, César still has one big, though unstated, problem: she is a precocious little girl trapped in the body of a boy.

So begins this strange novella by the Argentine writer César Aira. He has written more than 30 books, including a study of Edward Lear and a novel about a group of writers who decide to clone Carlos Fuentes, and has translated Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and Raymond Chandler. Until now only two of his novels had been translated into English, both tales of Europeans drawn into strange quests in 19th-century Argentina. The most recent was “An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter,” in which a German artist is struck by lightning and dragged face-down across the pampas by his horse. Aira’s sharp eye and supple imagination follow the artist after his accident, as he crosses the continent sketching gauchos and Indians, his mangled face hidden behind a black veil.

Despite the title, no veils or vows are taken in “How I Became a Nun.” Instead, Aira draws on a tradition of picaresque novels in Spanish that extends back to the 16th century. But he subverts the genre by allowing his narrator to escape from her daily life into a series of grandiose reveries. When she visits her father in prison, César crawls through a hole in the wall, imagining that “each successive incident, right from the start, from the moment I tasted the strawberry ice cream, had been leading me to this crowning moment, preparing me to be the angel, the guardian angel of all the criminals, the thieves and murderers.” When a word she deciphers on the wall of the boys’ bathroom gets her in trouble at school, she retreats to the attic to play teacher to a roomful of imaginary dyslexic children, then becomes her own pupil by giving herself minute instructions to accompany every waking act: “How to manipulate cutlery, how to put on one’s trousers, how to swallow saliva.”

These good works in the privacy of her own mind are the closest César comes to becoming a nun. In real life, however, she is a compulsive liar. She lies to the doctor who treats her for cyanide poisoning. She humiliates her mother on a public bus by asking, loudly and repeatedly, whether her father is dead when she knows he is not. Then she lets the reader in on the secret to lying well: “Pretend convincingly not to know certain things.” This habit of omission may be how she convinces herself that she is really a girl, although it’s not entirely clear that she’s deceiving herself at all.

Why can’t César face the truth? The closest she comes to an answer is when she says that after the poisoning “something had broken inside me, a valve, the little safety device that used to allow me to switch levels,” presumably between fantasy and reality. But she is also trying to escape from a body of the wrong sex and from a sense of guilt, however misplaced, over the ice cream vendor’s fate.

On another level, though, César’s ambitious delusions seem imposed by the author. Despite Chris Andrews’s clear translation, Aira’s prose seems hesitant, his imaginative flights clipped by the 6-year-old mind he is trying to inhabit. As a result, these perplexing episodes don’t quite add up to a credible story. But Aira does evoke a sense of childhood that is chilling and bittersweet — like a poisoned cone of strawberry ice cream.

Jascha Hoffman is on the staff of The New York Review of Books.